Reflections from Evelyn Landry, Former Deputy Director

Evelyn Landry discusses research initiatives underway to improve fistula treatment and care.

Reflections from Carrie Ngongo, Former Senior Program Associate

Carrie Ngongo wrote this Mother’s Day reflection in May 2009. She submitted an abbreviated version of this story to Nicholas Kristof’s « Half the Sky » Competition in The New York Times, in which readers were asked to contribute personal stories about their work with women’s issues worldwide. Her story was selected for an honorable mention out of over 700 entries.

This is my first Mother’s Day as a mother: I am blessed to have a delightful baby girl who is growing, learning, and thriving. Becoming a mother has certainly given me a great deal of appreciation for all mothers. I’ve also found myself thinking about women who have not been so fortunate on their road to motherhood and who instead have faced great difficulty and loss along the way.

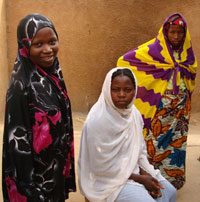

In March I had the opportunity to meet a group of inspiring women in Niger who had all been through traumatic labors. Each of these women had been eager to bring a baby into the world. They felt the joy of kicking in their wombs, and they talked to their growing babies as they went about their days, just as I did. Yet while I was in the care of an experienced doctor and delivered at a hospital in a major city, most of these women were in rural areas without the help of a skilled health provider. They labored and labored, but something wasn’t right: Their babies were not passing through the birth canal. By the time they were brought to a hospital for emergency care, it was too late. Their babies were dead.

This would have been loss enough, yet it didn’t stop there: They soon discovered that they were leaking urine, the result of obstetric fistula. They couldn’t control the flow, even if they tried not to drink much or used cloth to soak up the mess.

For some, their husbands and family members stood by them in spite of their smell, but many experienced rejection and isolation from those closest to them. Not only had they lost their babies, but they’d lost their health and their personal relationships too.

Fortunately, each of these women had found out that there was hope for them. Fistula can be repaired in most cases, and the women heard that surgical repair is available at Lamordé Hospital in Niamey. Lamordé is one of the hospitals supported by the Fistula Care Project, which EngenderHealth leads with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development.

At Lamordé Hospital there were 17 women who were hoping for healing. Lamordé has a structure set aside for women awaiting fistula repair surgery. It’s a plain building jammed full of simple bed frames, without power for fans or air-conditioning in the sub-Saharan heat. There’s space just next to it for women to cook or find shade to rest. Some of the women have been here for more than a month, waiting to be hospitalized for the treatment.

At first glance, providing fistula repair surgery seems straightforward. A trained surgical team in an equipped hospital is all you need—but it’s not so simple. In much of Africa, there are too few doctors to serve large, dispersed populations. Motivated surgeons need time to be trained and to advance their skills, especially because of the complexity of repair and the reality that no two fistulas are the same. One fistula surgeon in a hospital is often not enough, because that doctor may be called away. Moreover, fistula repair is never an emergency, and understaffed and overburdened hospitals can easily prioritize a thousand other important things.

As I talked with the women, I was amazed by their patience and endurance. These women have already been through plenty. How can we reduce the time they wait for surgery?

This was one of the subjects I discussed with the hospital staff who make fistula repair possible, including social workers, nurses, record keepers, and surgeons. We agreed that the Fistula Care Project will continue to train surgical teams and equip the hospital, so that client backlogs diminish over time. Together, we’re working on innovative solutions like supporting field trips for trained surgeons to travel between hospitals in order to pool their efforts, and encouraging hospitals to improve communication and record keeping in order to improve the quality of their services.

All 17 women whom I met in Niger have now had their lives transformed by fistula repair surgery. They are recovering, looking forward to returning to their homes and rebuilding their lives. Many hope to try to have a child again. Thanks to fistula repair surgery, they too may be mothers celebrating healthy babies on a Mother’s Day in the future.